Next-generation BIM developers are developing tools that automate the production of detail design models and downstream drawing production. While there are many ways to get there, the end-goal looks to be the same: models and drawings produced in minutes, not months

Momentum in the BIM 2.0 development community continues to grow. This month, industry veteran Martin (Marty) Rozmanith contacted AEC Magazine to give us a sneak peek of the next-generation BIM technology that he’s working on. This is highly unusual, since many folks prefer to stay in stealth mode. But perhaps it’s a sign of the times: the race for the soul of the BIM market is now truly underway.

Resumes can be dull, but Rozmanith has a solid background and has spent his career at the forefront of AEC tool development. He was technical product manager at Autodesk for Architectural Desktop between 1996 and 1999. He then left Autodesk to join a start-up called Revit Technology as director of product management.

With Autodesk’s 2002 acquisition of Revit, he was sucked back into the mothership, where he spent another three years, before leaving for a series of roles in manufacturing-in-construction startup companies focused on housing affordability and sustainability.

Next, Rozamanith joined Dassault Systèmes in 2012, at a time when the company was trying to build an AEC team. There, he put in a ten-year stint as sales director and then strategy director of Construction/Cities.

In other words, having been in the business for so long, Marty Rozmanith knows the industry back to front — and he believes that a small, motivated software team can bring new value and new applications to market faster.

In fact, his frustration with the glacial pace at which big software firms tend to operate has led him to join a smaller company as its chief technology officer (CTO). That company is Atlanta, Georgia-based Green Building Holdings, which began life as a decarbonisation consultancy firm some fifteen years ago. Today, its core business is LEED, BREAM and energy modelling services. It is headed up by Charlie Cichetti, one of the 300 LEED fellows within the 300,000-strong community of LEED certified professionals in the US.

Green Building Holdings is a group of companies, which also includes consultancy Sustainable Investment Group (SIG) and Blue Ocean Sustainability, a green building software lab focused on measuring carbon in construction. The latter is led by Kristina Bach, the first reviewer that the US Green Building Council hired to review actual projects. Within the wider group, there is also a training company called GBES (Green Building Education Services), which has trained some 150,000 of the aforementioned 300,000 US-based LEED professionals.

“One of the reasons I joined this team was they had started a competency in software and they had consultants and actual client projects that needed software that didn’t exist yet,” Rozmanith explains. “The other reason is that one of the co-investors in the holding company Green Building Holdings, I’ve known for thirty years now. Arol Wolford was one of the board members of Revit. He set up Construction Market Data back in the day and sold it to Reed Elsevier. He’s now pretty-well known in the capital space for AEC in North America.”

Blue Ocean AEC

After spending much of his career working at large corporates, what was the attraction of creating a start-up at this stage? I ask Rozmanith.

“I was talking with Charlie for a year, and he wanted to expand the mission of Blue Ocean and do something interesting. We are looking to address design, construction and eventually operation, but my focus this year is really working on the design side and starting a new brand, Blue Ocean AEC. We’re different because we create software by architects for architects,” he replies.

“From my experience, big software companies do consultative selling. They go in front of the customer, ask a bunch of questions, and try to find the hot burning problem that they can use to extract money from the customer there and then,” he continues.

And that’s always kind of fine. It’ll drive revenue once you have a mature product. But when you don’t have a mature product, it will just kill your customers, because nobody will want to work with you if that’s your thinking. Big firms are really focused on trying to drive revenue in the short term, because obviously, once they’re publicly traded, that’s what you’ve got to do. I think I’d sooner be at a private company, where we can kind of do the right thing.”

His plan is to replicate the go-to-market strategy used by Revit right at the start. In other words, get the first dozen customers and send them into bat for you, in different parts of the country. These initial customers act as ‘lighthouses’ that attract other firms and act as an advisory board to the company. “We can have an open conversation with them about what problems they are trying to solve and what are their priorities — because architects are willing to do that,” he says.

Talking automation

After talking about Swapp, Hypar and Augmenta, and the potential impact of AI, I ask what kind of design tools Rozmanith is looking to create. His response: the automation of drawings and design.

“I’m thinking about doing this procedurally first, because AI, although interesting, is somewhat unpredictable,” he explains. “In a creative sense, it’s kind of fun, but one of the things that comes to mind is something Patrick Mays [former CIO of NBBJ] always said: ‘An architect is a special kind of lawyer who makes contracts with drawings in addition to words.’ At the end of the day, when you must be paid to make a contract like that, you kind of want automation that’s predictable. I agree that AI is going to have a big impact on the market, but it’s not the only way to automate.”

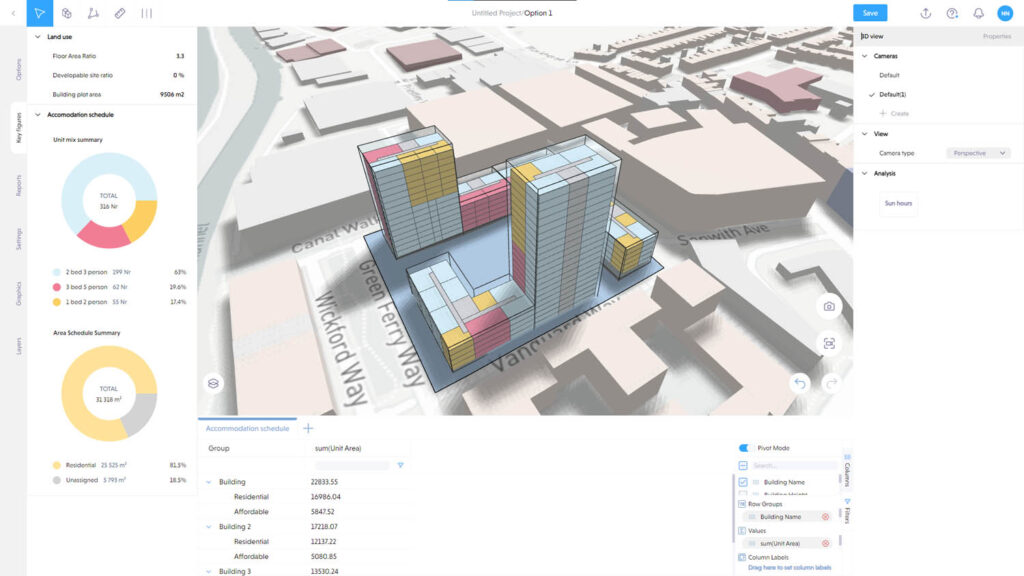

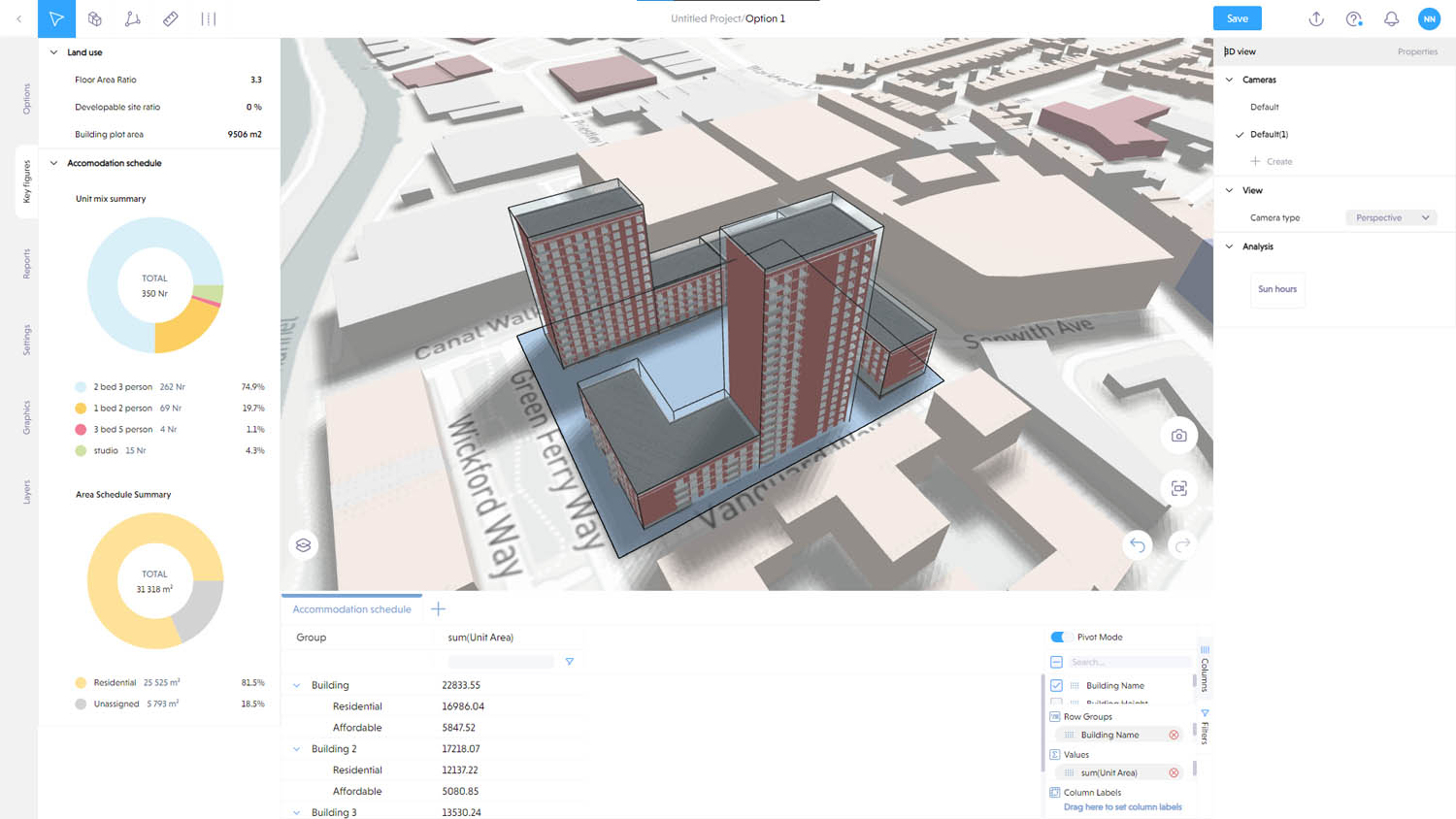

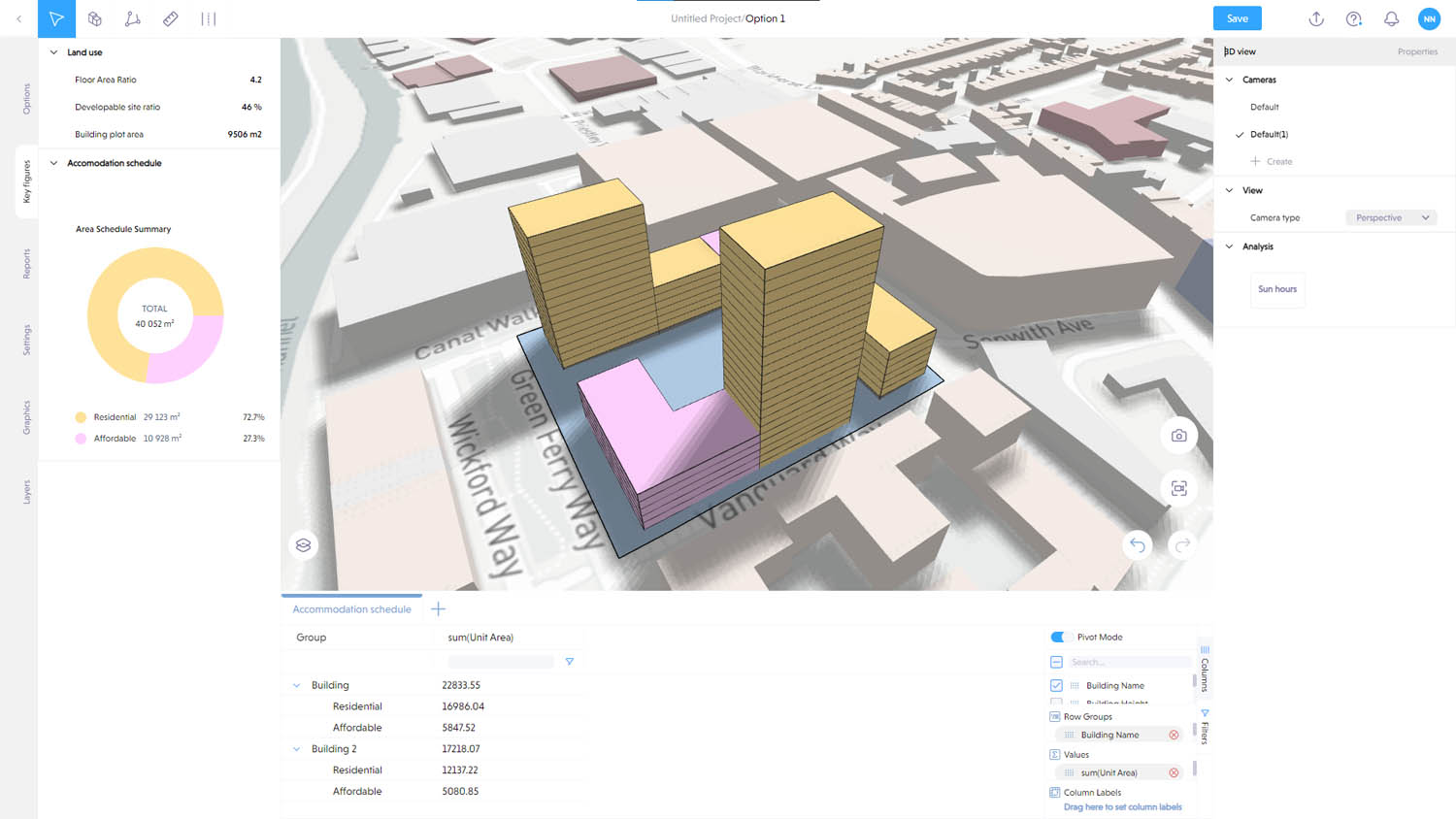

Blue Ocean AEC looks to combine data and recipes from old Revit projects with new conceptual tools, in order to meet client briefs and then quickly and automatically create new detailed Revit models

He recently attended the Design Futures Council 2023 event in La Jolla, California and there was a lot of talk about change among the attendees: that architects need to get away from pricing in hours, that they need to change the business model, use automation, learn to de-risk and so on. But all the people who were real change agents back in his early Revit days are the establishment now, he observes. “I have much better conversations at smaller firms than I do at big firms, because a lot of what’s coming next is going to hit architects in design and it’s not going to be optional to deal with it.”

Software development today is a “buy, build or partner” decision, according to Rozmanith. He’s choosing the partnership approach. “We’re a lab-to-market software house that isn’t really trying to push a box of something. We want you to be able to automate what you do, but we have some special tribal knowledge about that fifteen years’ worth of Revit data on your servers. And we can leverage that to automate what basically takes up 85% to 90% of your fee.”

Back in 2021, AEC Magazine covered Rozmanith’s presentation about a Dassault Systèmes project for Bouygues. Here, a new process reduced the design time by more than 50%.

“This required a lot of pre-planning to rethink how the building can be done using modules. And you figure out how those modules are assembled, which requires an entire team that doesn’t work on projects, like an elevator manufacturer would. And then you have some simpler tool that does general arrangement,” he observes.

“There’s an abstraction of the complicated, with blocks moving around in the general arrangement. Once you’ve resolved the general arrangement, you use that relationship to create the LOD 400 building model, based on what’s in the detailed modules. And that’s how they resolved getting a fabrication level model to go and execute the project.”

It’s an interesting idea, he says, “because not everyone needs to have to learn all the complicated stuff in Catia.” Obviously, you would still need a Catia team, but a wider group would benefit from using it.

But he sees a couple of problems with this approach. “If you’re the contractor, you could understand this and how this could make things faster. If you’re an architect, basically, none of the stuff you have right now helps you. Basically, you’ve got to throw everything away, rethink how buildings are done, along means and methods lines, which in the US, architects are prohibited from touching.”

In effect, only a contractor could do this, he observes, which is why Dassault Systèmes started with France-based Bouygues. Either way, architects get left out of the process, “unless they get hired here under the general arrangement.”

The second issue, as he sees it, is that you have to figure out modules ahead of time. “You can’t really use this for an engineer-to-order construction process, which is 95% of what’s going on right now. You can only use it for configure-to-order. And you really have to rethink how buildings work, like Katerra would do to make them configure-to-order. There’s a lot of constraint and everyone’s had a lot of upfront work.”

In the meantime, developers have been getting funding for tools that handle the general arrangement aspects, such as Spacemaker.

Perkins and Will came up with Massformer. LendLease had Podium.

“There’s a theme here,” he laughs, “but I think they didn’t kind of get the big idea. Because you can’t do the contract from these tools. They don’t produce any data that you can use. If you create a layout in Spacemaker, go get a bunch of cubes in Revit, then you have to figure out how the building’s going to work. What I’m working on is similar in concept to what I originally described, but the idea is you use the simple layouts to generate the LOD 350 models, so you can do automated construction drawings.”

Skema.site

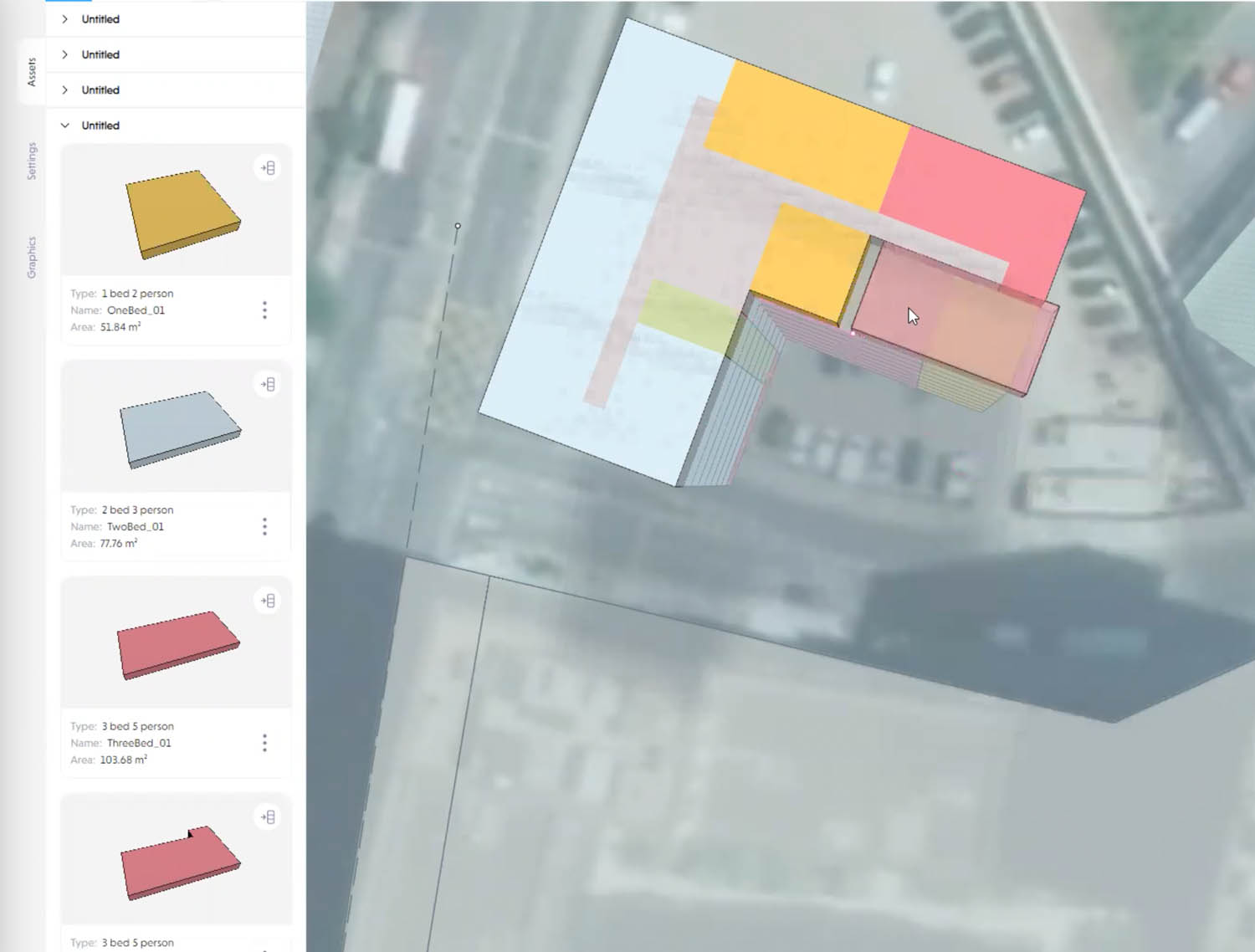

As the front end for design, Rozmanith and team at Blue Ocean AEC have developed a cloud-based tool called Skema. If you take the example of a parking garage, the creation of a 2D layout would be driven by where its parking spaces and aisles lie. There’s a simple app that helps the user figure out where they want the ramp, in which direction it should go, where spots for disabled drivers should be situated, and so on.

“And then it generates a 3D building based off of that, all at LOD 350,” he says. “We have a link to Cove.tool to do analysis. It has the same kind of Element Classification you would find in IFC or Revit. You can assign costs, if you are a contractor, for reports. But the main thing is that we manage that LOD 350 model in the systematic generation at its back end, so it has one-to-one correspondence with Revit.”

That means it can be pushed into a Revit model so that it’s well structured. “It would act just as if you had created it in Revit. You can change it, you can do whatever you want with it. And that’s the starting point for then doing automated construction documents,” he says.

“We’re showing this just as a concept in the early phases, but as we create the detailed data, we will have other analysis engines that get increasingly accurate as we get higher LOD. The main part of the system is figuring out how space should fit into a volume. Whether you sketch that volume, or you create that volume with some other Grasshopper-driven tool or something like that, we don’t really care.”

The original team that wrote this code (www.kreo.net) was located in Belarus with headquarters in London. When the Ukrainian war broke out, the Belarus team relocated to Poland. Currently, the team members of Blue Ocean AEC’s R&D partnership are in London, Poland, and the U.S. They are working on abstracting the historical layout data from an architect’s past Revit files, over 15 years’ worth, and fitting those into the actual volumes created via an adjacency matrix in Skema, while altering them parametrically to fit whatever shape future projects may take.

This seems not dissimilar to Finch3D, but maintains LOD 350. Rozmanith explains further: “If you are designing a school, we’ll look at three or four schools from your past school designs and capture the arrangements from Revit. We basically farm the data out of the old Revit projects to create these layouts that are abstracted into 2D, then use Skema to go and take those arrangements and fit it into whatever site is being worked on.”

The idea behind Blue Ocean AEC’s Skema is that it will speed up time and deliver multiple alternatives for the user to explore. When they narrow it down, they can go and look at the detailed buildings that are generated in literally minutes, reconstituting a new model out of previous Revit data. Models will be a combination of layouts that they’ve done, and some blank space blocked out for elements that need to exist, but haven’t been laid out yet.

“We’re not using AI for this part. This is all procedural, it’s very predictable,” says Rozmanith. “Our goal is to automate 60% to 70% of the layout of the building, so that we get rid of the boring stuff, leaving the lobby and the signature spaces and the atrium and all that stuff, which you as an architect really want to work on.”

Conclusion

There is undoubtedly an opportunity to improve productivity in AEC and there are now many developers looking to automate design and drawing production. But from talking to them all, there seem to be many ways to skin this particular cat.

Blue Ocean AEC may be some way away from bringing its product to market but it looks to combine data and recipes from old Revit projects with new conceptual tools, in order to meet client briefs and then quickly and automatically create new detailed Revit models. The recipes for these stay in Skema.site, where they can be edited and regenerated in Revit on demand.

The company’s green expertise will also make some appearance in the process, to further refine designs to meet ever-stringent sustainability goals. Rozmanith doesn’t look to replace Revit, but instead use it as a documentation engine. And by keeping all that data at LOD 350, this will save a lot of work.

We hope to have Rozmanith and his development team at Blue Ocean AEC join us in London on 20 June at NXT BLD and NXT DEV.

The trouble with offsite

One of the drivers for next-generation BIM is the need to connect design to fabrication. But today’s BIM systems were never intended to do that. And while developing a tool that can handle ’loosey-goosey’ geometry is one thing, refining it to fabrication level is quite another. Plus, there seem to be big issues in getting offsite construction firms up and running and financially stable.

Rozmanith has seen this issue from all sides. “The AEC market is harder than the MCAD market, and if there’s one thing I’ve seen more than once, it’s that finance people will underestimate the scope of the problem,” he observes.

“They think it looks simple and then they will burn a lot of money and go out of business. We all watched Katerra burn through a billion dollars. It seems that firms entering this market think that having the manufacturing facility is the first step, when it is the last step. You figure out everything before you go and build the manufacturing facility,” he says.

“I’ve talked with big firms that spent millions on building manufacturing facilities and six months later were saying ‘It’s not running very well, we need help.’ Then we came in, and they couldn’t even tell us what their processes were, because they hadn’t figured them out yet!

Unfortunately, he observes, construction companies get a one and a half times multiple of revenue as a valuation on the stock market, while a tech division can get a thirty times multiple on the stock market. “Offsite is seen as a way to say they have a tech division, because of that. It’s a really bad idea for construction companies to make software, because it’s not their core competence. A thirty times multiple of zero revenue is not really a very good outcome!